WINNING THE LOSER’S GAME: The Creator Economy and the Companies We All Need to Build

My Creator story and what it's taught me about the future of companies and the opportunity we have to build them.

Check out these popular articles:

"I submit that tennis is the most beautiful sport there is and also the most demanding. It requires body control, hand-eye coordination, quickness, flat-out speed, endurance, and that weird mix of caution and abandon we call courage." David Foster Wallace

I. THE AMATEUR’S GAME

I submit that building a company is the most beautiful profession there is and is also the most demanding. It requires mind control, emotion-to-execution coordination, decisiveness, patience, quickness, and that weird mix of collaborative and communicative capacity we call leadership.

John Brewton

I began playing competitive tennis when I was in sixth grade, became serious about the sport, choosing to leave baseball behind to pursue the solitude of competitive, clay court glory in middle school, and ultimately become a top USTA player in my region and the number one singles player on my high school team, where we won three WPIALL championship in my four years of attendance. We would have won four, but I lost my match in the league finals my freshmen year.

The tennis court is where I learned how to learn from losing, how to win when loss seemed certain, how to lead a team, how to prepare, how to manage emotional turmoil, how to adjust strategies, how to fight through physical pain and the limits of what I perceived I could physically and mentally accomplish.

The tennis court is where I learned everything I would ever need to know about building a team, leading a team, choosing a strategy, executing on a strategy. It’s where I learned all that would be required to build, operate, optimize and grow companies.

In his classic Winning the Loser’s Game, Goldman Sachs luminary and Greenwich Partners founder, Charlie Ellis, starts with a simple observation about amateur tennis:

At the professional level, tennis players win points. They hit blistering forehands down the line and 130-mile-per-hour serves that clip the edge of the box. The game is about hitting winners. The game is about the triumph of skilled execution.

At the amateur level, points don’t end with heroic shots…they end with unforced errors and maybe a thrown raquet or two:

Someone hits the ball long.

Someone dumps a backhand into the net.

Someone double-faults.

The way to “win” the amateur game is not try to hit like Federer, it’s to make the fewest errors. The aim must be to stop beating yourself. To become Roger Federer, you must first learn how to stop losing.

Ellis’s punchline is that most investing is the same. For the typical investor, trying to pick stocks and time the market is a loser’s game. You don’t need more winners; you need fewer errors. That’s why boring, low-cost index funds quietly outperform most attempts at genius.

My punchline is that the entrepreneurial, founder, and business building journey follows the same cadence.

I spent my twenties and thirties learning how to play and win the Loser’s Game of business on my way to turning pro.

I studied economics as an undergraduate Harvard, before heading to graduate school at the University of Chicago. Then, on the advice of a professor, I went home Pittsburgh and did something decidedly unsexy: I became a Sourcing Specialist, then an Operations Analyst, then Director of Operations, then CEO of my family’s industrial distribution company. Over the next decade, I helped optimize it, scale it across the United States, Mexico, and Costa Rica, became CEO, maniacally managed the org to EBITDA, dreamt night-after-night of multiples achieved, and ultimately sold the business in August of 2021.

Industrial distribution, as is true of most any B2B marketplace, is not a game of viral winners. It’s a game of fewer errors. It’s about inventory turns and truck routes, credit risk and cross-border logistics, margins measured in basis points, and customers who care far more about reliability than charisma. It’s also profoundly a competition over price and cost controls.

You win by building systems that quietly keep the ball in play every single day. And when you’re David competing against Goliath, it’s definitely cliché to say, but you win on quality of service, quickness of problem-solving, and quantity of problems solved.

After we sold the company, I knew I wanted to build something new. I started a consulting firm that advises small-and midsize industrial companies on strategy, operations, and technology. The work was meaningful, but the model was not: too much travel, too much dependence on my time, too little scalability. I had built a business before; now I had built a job.

So 18 months ago, on a random Tuesday, I made a change. I wrote a post…

II. ENTERING THE LOSER’S GAME

I started from zero followers on LinkedIn in March 2024 and decided to build a personal brand. Gary Vee had been telling me to do that for years, so I finally decided there was no better time than the present to get started. The first signal came quickly: a post about Andy Grove’s High Output Management. Nothing flashy, just a reflection on operational excellence, and it landed with 300 likes, 100 comments, and 8 reposts. It was modest by social media standards, but it taught me something electric: followers could be built. Attention could be drawn and grown.

Intel reacted to and commented on the post, which pushed it out to many of their employees, growing reach to over 90,000. I had gone viral! At least that’s what it felt like.

For months, I posted independently, chasing that same result, but more importantly, loving the process of writing each day. It became an opportunity to re-learn, re-read , re-understand so much of what had informed my approach to operating companies for twenty years. Each post felt like an opportunity to meet new people, to learn something new, to get better each day in the smallest ways.

I took Justin Welsh’s course on personal brand building that July. I went through the Ship 30 for 30 program (highly recommended), designed to sharpen online writing. Both were valuable, I learned structure, posting cadence, consistency and I began to build a small community of new friends going on the same journey. Though my audience was not yet compounding.

But I was still optimizing for the wrong scoreboard.

And then came the game-changer: Chris Donnelly’s Creator Accelerator. Here, I learned to design beautiful infographics, carousel posts, visual narratives that could stop a scroll. It worked. My following began to grow. Over the next year, I accumulated more than 20 million impressions on LinkedIn, and grew a following of +30,000 people. I also befriended Will McTighe and had the priviegle of being an early user of his incredible LinkedIn content creation software, SayWhat.

A handful of my posts went legitimately viral over this period and most began consistently performing very well. My following grew to 10,000 then 20,000 and now sits close to 35,000.

By every metric of the loser’s game, I was winning.

Overnight, my scoreboard had changed. But instead of revenue, margin, and cash flow, I woke up thinking about impressions, followers, and engagement rates. In other words: I left a world where I knew how to play the operator’s game, and wandered straight into a loser’s game without realizing it.

The trap is so subtle because the vocabulary of “growth” sounds familiar. I knew how to scale a business. But I wasn’t yet focused on the difference between building an audience and building a business with an audience.

III. A $480 BILLION MARKET, AND A LOSER’S GAME FOR ALMOST EVERYONE

With time, here’s what I began to notice: I had 30,000 followers and no clear way to monetize…no clear way that was any different than the unsustainable consulting model I had been building. Yes, clients came in, but my life wasn’t better. In fact, it was worse, because now I had a full-time content creation and brand-building job along with my consulting work.

Stress multiplied.

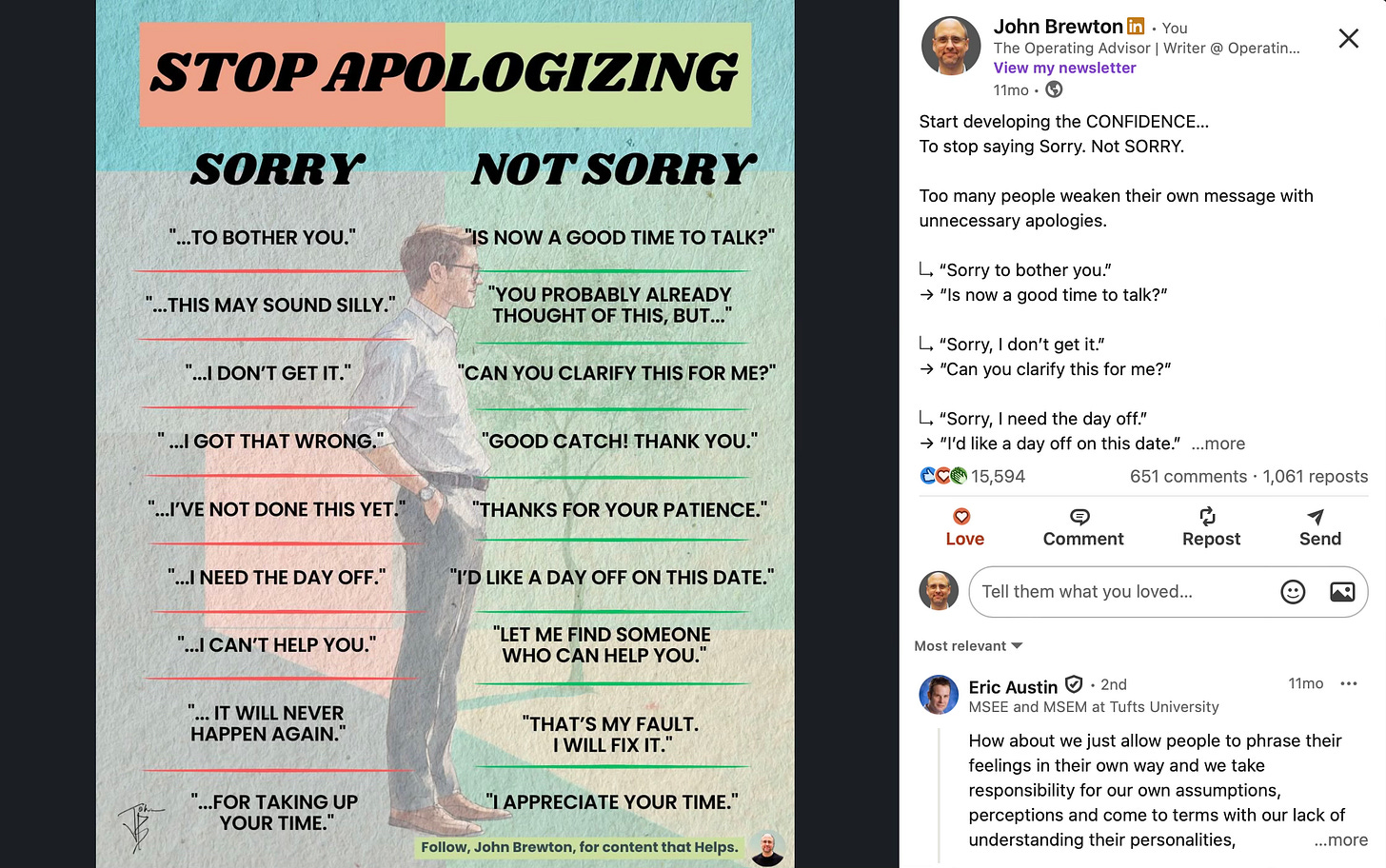

I had become very good at one specific, very tactical skill: making content that performed well on LinkedIn’s algorithm. I could tell you the optimal post length, the best time to publish, which visual patterns would get engagement. I had mastered amateur tennis and graduated to hitting beautiful shots that looked impressive in the moment, but were not helping me win entire tournaments.

I had not built a business.

Does this sound familiar?

This is where most creators get stuck. They’ve tasted the dopamine hit of virality. They’ve seen the follower count climb. They’ve gotten validation from strangers on the internet. So they optimize harder, post more frequently, chase bigger audiences. They’re still playing the loser’s game.

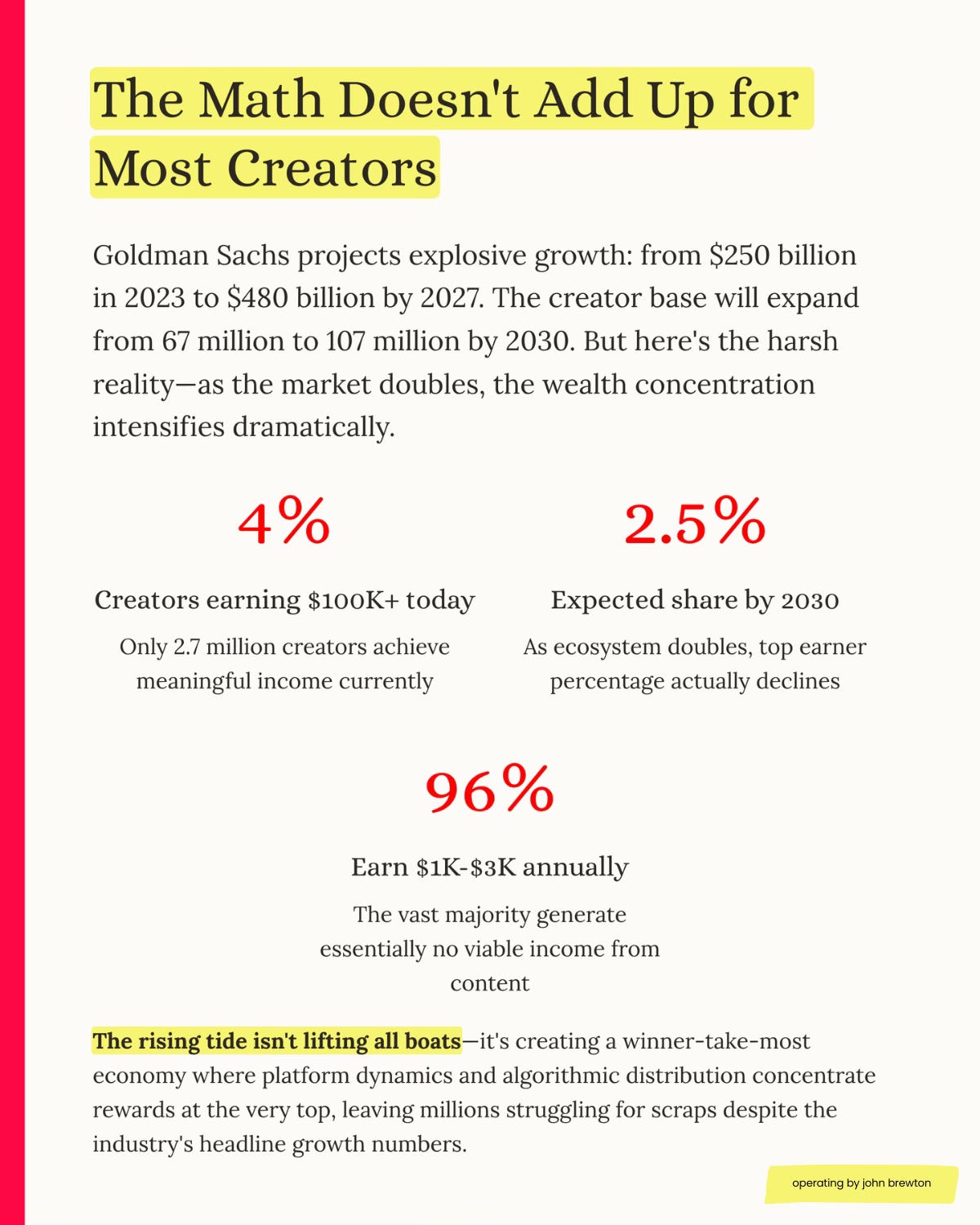

What I didn’t realize at the time was that my experience, frustrating as it was, had become entirely predictable at scale. Goldman Sachs looked at the creator economy and published research that essentially validated Ellis’s loser’s game thesis using hard numbers.

This a massively competitive market (Lottery?) with increasingly brutal odds.

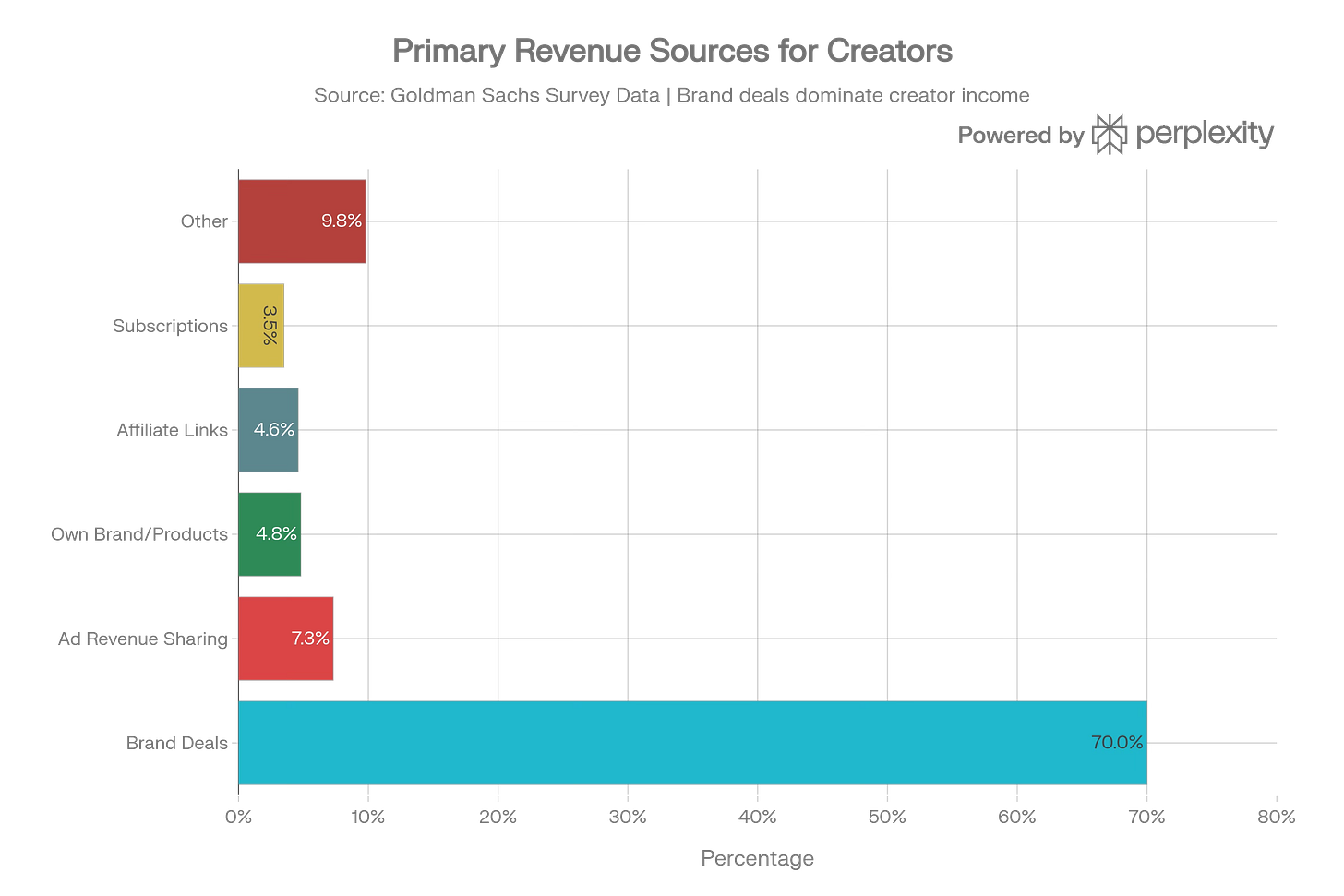

Goldman’s analysis breaks down creator income into three buckets: Roughly 70% from brand deals (sponsorships and affiliate relationships), about 7% from platform ad revenue sharing, and the remaining 15–20% from audience-directed monetization, subscriptions, tipping, merchandise, and direct-to-consumer sales. That 70% number matters. It means most creators are betting their entire business on a single, highly concentrated, highly cyclical revenue source they don’t control.

The concentration is staggering. Goldman’s data show that the top 10% of creators now receive 62% of brand ad payments, and the top 1% alone capture 21%. As the overall market grows, income doesn’t distribute evenly across the expanding creator base, it concentrates at the top. In other words, as the market scales, the middle hollows out. The power law gets steeper. The odds get worse.

In the creator economy, most people lose because they’re playing the influencer’s game, chasing brand deals, optimizing for followers, and depending on platforms they don’t own. Structurally, that game is rigged. The house wins. The individual creator nearly always loses. The time-for-compensation trade doesn’t generally work out in the creator's favor.

This wasn’t some failure of will or strategy on my part. It was me trying to win a game where the odds are mathematically against 96% of participants. Had I been advising a founder in a business with similar economics, I would have encouraged them to exit the market altogether. But in my zeal to learn how to do something new and continue creating content that performed, I was lost to see the proverbial forest-for-the-trees.

IV. THE OPERATOR’S GAME: FEWER MISTAKES, NOT MORE WINNERS

As this reality became clear, I shifted my thinking. I need to stop trying to become influential and needed to build an actual business to operate. The content was and is critical, but it is simply part of a larger operating structure.

What value did I want to provide?

More than anything, I like to help people solve problems.

It’s selfish. I like how it makes me feel.

The problems I’m best at solving are all related to how companies can operate more profitably. I started from zero again with Operating by John Brewton on Substack. I wanted to write about the history, economics, and future of operating companies to help founders, builders, and operators build better companies.

And that’s where the work has led me today.

I still have a group of traditional consulting clients, but I am trying to build an actual business around Operating by John Brewton.

Specifically, I want to help as many creators as possible build sustainable, profitable, growing, small companies. I want to learn firsthand the extent to which large companies can be built and scaled with fewer people than was previously possible, given the AI-first era we are living through.

How about you?

Building a business when you are solely responsible for every part of the organization, every offer, every piece of delivery, is a different kind of hard.

There’s no CFO to tell you if your unit economics work.

There’s no Operations team to systematize what works.

There’s no HR department to hire the people you need.

College doesn’t teach you how to build a company.

Experience and lots of failure is responsible for that learning.

It’s just you, your time, and the decisions you make about how to allocate your personal, finite resources.

I want to use my experience, failures, education and compounded, strategic sensiblity to help build the next generation of great creator businesses.

Sidebar: What I Think We’re Getting Wrong

Our feeds, conversations with friends, and streams are filled with noise selling us on an apocalyptic narrative. We’re inundated with stories about layoffs, the inevitability of our skills, jobs, and unique capabilities being replaced, done better and more cheaply by AI. We’re told that we will need to adapt to a world where our governments grow ever-larger in an effort to subsidize the incomes, healthcare and basic needs of the populations they serve and protect, because the robots are coming, all the jobs are going away and there is simply no means by which any person, from square one, can compete and win in a world this unfair, this rigged, this unequal. We’re being told to be scared and it’s working.

I don’t negate the truth of growing inequality, the rising expense of becoming traditionally “well-educated,” or the difficulty of finding a new job, but I also think we have a choice. I believe we all have the capacity to create and build something new for ourselves, our friends, our markets, our families, our world. I believe it’s never been easier, or more necessary, to start, grow and scale a business.

I believe the companies we build right now have the opportunity to become the great companies and brands of the new future we’re building. Changing times create a culture that wants something new. Changing technology gives builders the opportunity to build something new. Changing constraints and demands ask us to try something new. Change and new go together.

VIII. INSTITUTIONAL BACKING: WHY THE INCUMBENTS WIN, AND WHY YOU DON’T HAVE TO

It’s worth understanding who actually captures most of the value in the creator economy. The answer might surprise you, because it’s not individual creators.

Meta, YouTube, Amazon, and other major platforms are the structural winners. Goldman Sachs identifies six key competitive advantages these incumbents possess:

Massive scale (2–2.5 billion users each),

Diversified capital for creator payouts,

Sophisticated AI-powered recommendation engines,

Multiple monetization tools,

Granular analytics,

Integrated e-commerce.

These aren’t advantages a solo creator can match (but we can leverage these tools for our own benefit). They’re systemic.

What this means in practice: the platforms have already won. They will continue to concentrate value. The algorithm will continue to favor the top 1% of creators. The brand deals will continue to go to the mega-influencers. The venture funding will chase “creator economy solutions,” but most of those startups will struggle to find defensible models.

But here’s the crucial insight: you don’t need to win the incumbents’ game.

You don’t need Meta to pay you more. You don’t need YouTube’s algorithm to favor you. You don’t need brand deals or sponsorships. You don’t need to be on the “Breakthrough Creator” bonus list.

You need:

A small group of people who trust you.

A clear problem you solve for them.

A repeatable system to deliver that solution.

Ownership of the relationship (email, direct communication, not algorithmic distribution).

The platforms will continue dominating the creator economy TAM. But the operator’s game, the small real-business game, is played on your own terms, outside the winner-take-most dynamics, with much better odds.

Note: It’s also worth noting that if you’re willing to play the long game across the seven major social platforms, you can absolutely become a top 1% creator on any of them. And if you’ve built a sustainable, strong business in the mean time, that ultimate leverage can enable true scalability. The shift from follower-based to interest-based feeds and algorithms is also essential to understand to exploit.

IX. THE FUTURE YOU’RE ACTUALLY BUILDING

Goldman Sachs notes that high-earning creators average 7+ revenue streams compared to just 2 for low earners. The differentiation isn’t that they’re smarter or more creative. It’s that they’ve deliberately built a portfolio of income sources that don’t depend on any single platform, trend, or brand deal.

This is what an operator-creator business looks like over time:

Core content (newsletter, YouTube, podcast) as customer acquisition and thought leadership

Core offer (course, cohort, advisory, productized service) as primary revenue

Complementary offers (affiliate partnerships, affiliate income, speaking, workshops) as secondary income

Brand partnerships, if they align, as opportunistic income—not the foundation

You’re building a moat through specificity, through systems, through time. You’re not trying to beat Meta at the algorithm game. You’re building a business that would work even if all the platforms disappeared tomorrow.

This is the operator’s way. It’s not sexy. It doesn’t get featured on TechCrunch. But it’s the only sustainable path to the freedom and financial security that most of us actually want.

X. CLOSING: REDEFINING WINNING

Everyone starts by learning to win the loser’s game:

Roger, Novak and Rafa started by learning to keep the ball in play, their serves in the service box.

23 learned how to put the ball in the hoop.

Jobs learned how to sell the first Mac.

Bezos learned how to sell the first book online.

Goldman Sachs looks at the creator economy from 30,000 feet and sees a half-trillion-dollar market forming by 2027, hundreds of millions of people calling themselves creators, and a tiny minority capturing most of the income. From that vantage point, it looks like a powerful new asset class and a fertile hunting ground for Meta, Alphabet, and Amazon.

But here’s what Charlie Ellis also showed: You don’t have to play that game. You don’t have to hit winners. You just have to learn to keep the ball in play, across your core content, core offer, complementary offers, and brand partnerships.

The creator economy doesn’t need more influencers trying to win the wrong game. It needs more operators quietly building sound, small businesses behind their work.

The larger economy needs creators to build the next generations of great businesses. We live in changing, fraught times. And, we live in a moment of extraordinary potential. We live in a time that needs more companies, more founders, more executed ideas, more creativity, more new answers.

If you’re struggling to find your next job or first job..

Start building the company that will employ you.

If you’re worried about losing your job…

Start building the company that will never lay you off.

If you’ve been laid off, I’m sorry…

Start building a future where that will never happen again.

You can start right here on Substack.

You can start this morning.

You can start tonight.

But please don’t start tomorrow. Please just start.

I hope this helps. Most importantly, thank you for supporting my work by taking the time to read this article.

- john -

If you’re interested in talking, please send me a message. If you’d like to work together on building your company, let’s get started.

Author’s Note

This article grew out of eighteen months of learning to build a business in the creator economy—first chasing metrics and followers, then learning to chase customers and cash flow instead. The financial data from Goldman Sachs’ institutional research gave me a way to quantify what I was experiencing: that the default game is structurally stacked against the vast majority of creators, and that the only rational response is to opt out and build a different game entirely.

If you’re building something, I’d love to work with you. Become an Operating Founder at Operating by John Brewton to get your first four 1:1 60 minute strategic operating sessions for $99.

John Brewton documents the history and future of operating companies at Operating by John Brewton. He is a graduate of Harvard University and began his career as a Phd. student in economics at the University of Chicago. After selling his family’s B2B industrial distribution company in 2021, he has been helping business owners, founders and investors optimize their operations ever since. He is the founder of 6A East Partners, a research and advisory firm asking the question: What is the future of companies? He still cringes at his early LinkedIn posts and loves making content each and everyday, despite the protestations of his beloved wife, Fabiola, at times.

Such a timely and relevant article given how much creator economy has expanded and how much competition has exploded. Yet the fundamentals remain the same. Virality rewards even less in the long run, probably. Consistency and owning your audience, while diversifying audience platforms and income - that's where it's at!

John, this is a masterclass in applying Charles Ellis’s "Loser’s Game" logic to the creator economy. In a world obsessed with "hitting the jackpot" through viral spikes, we often forget that the most sustainable strategy isn't making the brilliant winning shot, it’s simply avoiding the unforced errors. Most creators flame out not because they lack talent, but because they violate the basics of consistency and audience trust. By focusing on "not losing," you’re essentially advocating for a high-integrity, low-ego approach that prioritizes longevity over the dopamine hit of the algorithm. It’s a sober reminder that in the long run, the "winners" are often just those who were disciplined enough to stay in the game while everyone else was busy chasing outliers.

Really good stuff, John.