Easy to Start, Hard to Win: What 50 Years of Economics Research Tells Us About Building Creator Businesses

Scaling Down the Big Ideas: Translating Academic Insights Into Action For Solo Founders and Small Businesses

In 2026, I’m working directly with 100 creators building real businesses.

I want to bring operating strategy, competitive positioning, and financial planning to a community that’s fundamentally different from my typical industrial and technology clients.

For the first 100 creator founders: Four 60-minute 1:1 advisory sessions for $95.

Context: My standard engagement starts at $10K/month. This isn’t that. This is me learning from you while helping you build something sustainable.

Limited to 100 spots. 63 of 100 have filled. Offer expires this Friday, February 6th at midnight. And once it’s gone, it will not be returning.

Start Here

I built my creator business from zero to 4,000+ Substack subscribers and 55,000+ followers across platforms in under two years. By every measure, entry was free, Substack costs nothing, LinkedIn is virtually, and the barriers to starting to create content and building a personal brand are nominal.

Yet I’d tell anyone who asks that all hyper competitive markets with low barriers to entry have high barriers to success.

This paradox confuses most founders. Economic theory can help us strategize against his truth, if you know where to look. I spent my twenties in academia, tirelessly studying economics so I could help you today. Four landmark papers, spanning five decades, articulate why markets with low barriers to entry develop extreme barriers to success. And building a creator business forces you to confront all four. Today, I’m going to scale these complex ideas down to what’s actionable for solo-founders, creators and small business builders.

Hope this helps!

- j -

In 1977, economists Avinash Dixit and Joseph Stiglitz built a model of markets where entry is free, products are differentiated, and firms compete for consumer attention. Their conclusion: when anyone can enter, competition drives profits to zero. Everyone earns just enough to justify the work, no more.

This is the creator economy in a single sentence. Substack has 2 million+ writers. YouTube hosts 114 million+ channels. When platforms eliminate entry barriers, the average return collapses toward zero. Most creators earn under $100 per month. Free entry guarantees crowded markets and fierce competition.

But here’s what Dixit and Stiglitz couldn’t explain: why some creators break out spectacularly while most languish. Their model assumed symmetric firms, everyone identical in cost structure and consumer appeal. In reality, creator success looks nothing like this. A tiny fraction captures the majority of revenue. The distribution is winner-take-most.

The next three papers explain why, so you can become one of the winners who “takes most.”

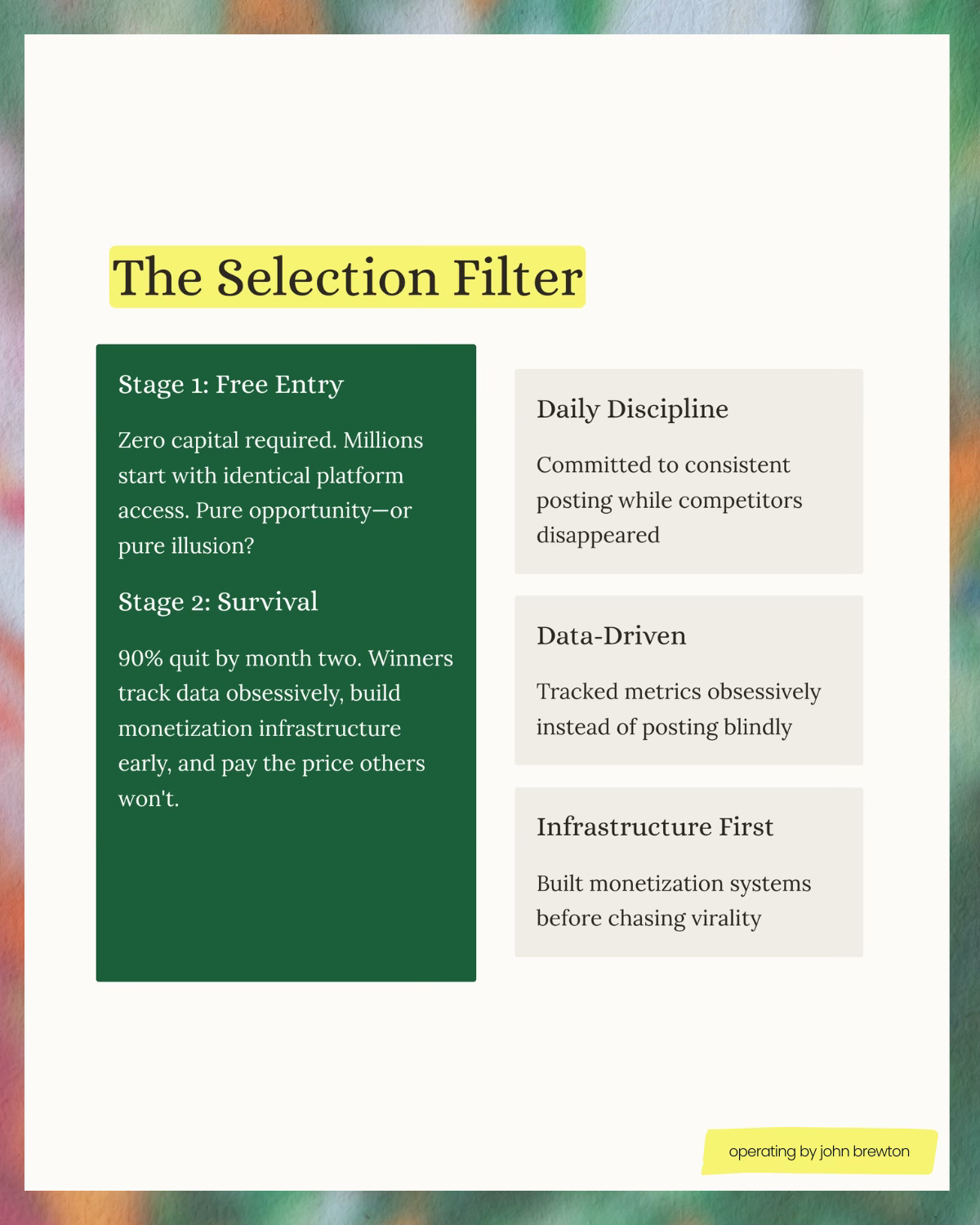

Hugo Hopenhayn’s 1992 paper modeled industries where firms enter with uncertainty about their productivity, then discover whether they can survive. Low-productivity firms exit quickly. High-productivity firms survive and grow. The result: many small failures, few large winners.

This maps perfectly to creator businesses. Most newsletters lose 90% of subscribers in Year 1. Most YouTube channels quit after fewer than 10 videos. The distribution is extreme not because of luck, but because of selection pressure.

But here’s where Hopenhayn’s model breaks down for creators: he assumed productivity was random, a luck-of-the-draw attribute firms discover after entry. In the creator economy, productivity isn’t luck. It’s built through discipline most entrants won’t sustain.

When I started, I made a decision that changed everything: I would post every single day for one year, no matter what happened. Not “post consistently.” Not “post when inspired.” Every single day for 365 days.

This is the commitment that separates people who build something lasting and financially meaningful from people who quit in Month 2.

In my first 30 days, I posted into a void. Three likes. Sometimes one. Sometimes zero. My follower count barely moved. I wondered if anyone even saw what I was publishing.

This is normal. This is the process. This is the selection mechanism at work.

Social media algorithms reward presence, not perfection. In the first 90 days, you’re training the algorithm to understand what kind of content you create, who engages with it, and when they engage. If you post sporadically—three times one week, zero the next, five the following week—the algorithm never gets enough signal to optimize.

If you post daily, the algorithm has data. Data creates momentum.

I tracked every post obsessively: content type, platform, reactions, comments, shares, impressions, reach, time published. After 30 posts, patterns emerged. After 90 posts, I knew my formula. Without tracking, you’re guessing. With tracking, you’re learning.

Month 1, I published a post about Andy Grove’s book High Output Management. I made it vulnerable, I talked about my own mistakes managing teams, the lessons I was learning the hard way. The post got hundreds of reactions. Intel commented, which pushed it to their entire employee network. I added my first significant followers.

Then nothing similar happened for six months.

That’s the part nobody tells you. You’ll have an early win that shows you what’s possible. Then you’ll go right back to the grind, posting into the void, wondering if it will ever happen again.

It will. But only if you keep going.

Hopenhayn’s model explains the selection dynamic: most firms exit because they lack what’s required to survive. For creators, what’s required isn’t technical skill or initial quality. It’s the willingness to show up every day when nothing is happening.

That discipline is your productive edge.

The Sorting Year: What We Learned From 2025 & Where We’re Going in 2026

WINNING THE LOSER’S GAME: The Creator Economy and the Companies We All Need to Build

The commitment to post daily for a year wasn’t a productivity hack. It was paying an endogenous sunk cost—an investment that only makes sense if you stay in the game.

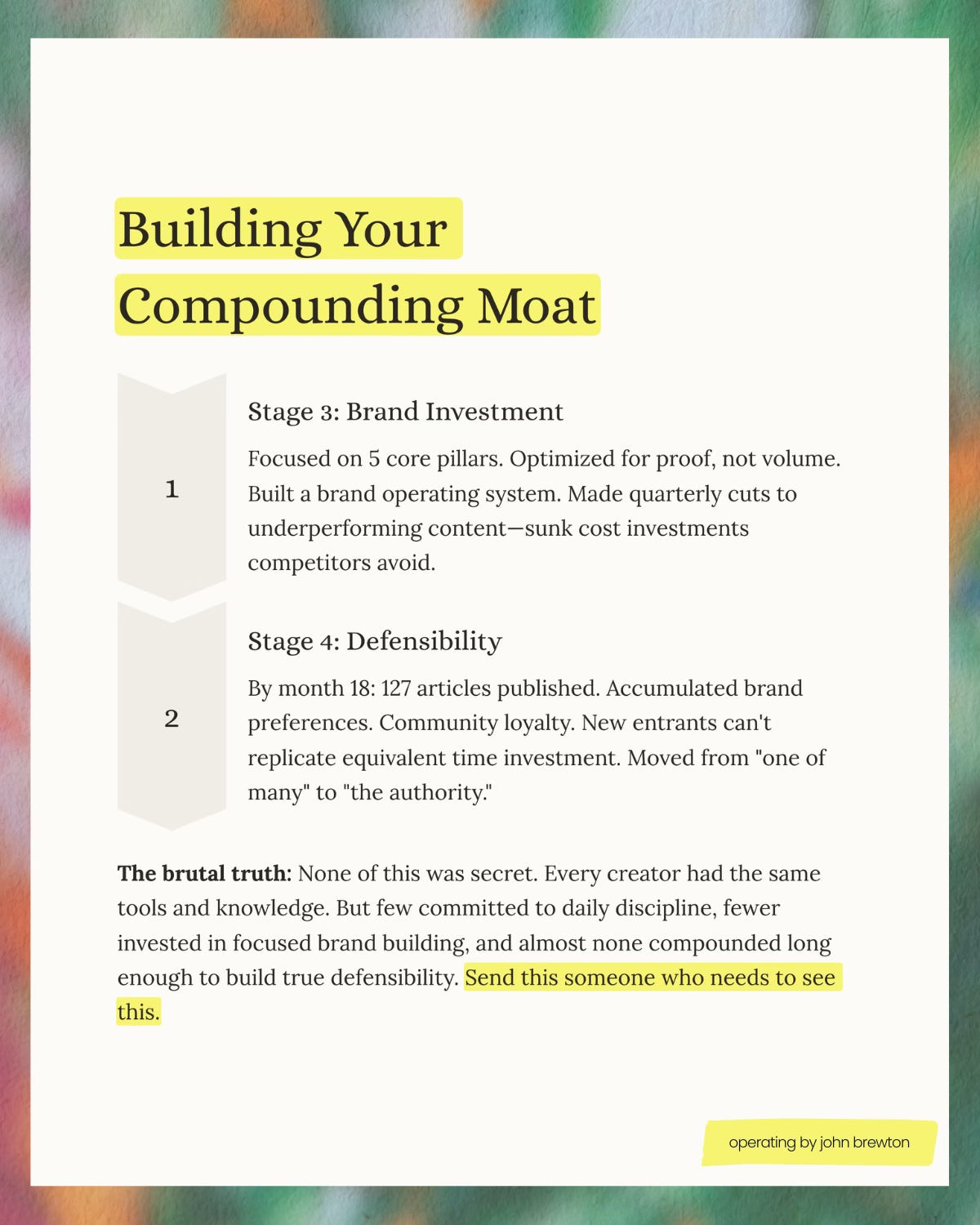

John Sutton’s 1991 work on sunk costs and market structure proved something counterintuitive: when success requires ongoing investment in brand-building or quality, markets don’t expand with new entrants—they concentrate around those willing to invest most.

Sutton distinguished between exogenous and endogenous fixed costs. Exogenous costs are barriers you must pay to enter: manufacturing equipment, regulatory compliance, physical infrastructure. Endogenous costs are investments you choose to make: advertising, R&D, brand-building. These costs don’t block entry, but they determine success after entry.

His key finding: in markets with endogenous sunk costs, concentration stays high regardless of market size. As markets grow, firms don’t just enter—they escalate investment. The result: bigger brands, not more brands.

Consumer packaged goods prove this. Anyone can manufacture soap or cereal. Entry barriers are low. Yet the top 10 brands control 88% of market share. Why? Because winning requires advertising investment that scales with market size. Most entrants never make that investment.

For creators, the parallel is precise.

Starting a newsletter is free. Succeeding requires sustained investment in brand capital—investments that are worthless if you quit:

Daily content creation (Twitter, LinkedIn, Substack)

Weekly newsletter consistency

Building email list infrastructure

Community engagement (comments, DMs)

Platform algorithm optimization

These are endogenous sunk costs. You invest time and money that evaporate the moment you stop.

After six months of daily posting, I joined a high-ticket cohort focused on visual content design and platform strategy. I invested $5,000 and 40+ hours per week, nights and weekends, while working my primary consulting job. I was working 80-90 hours per week total. It was brutal.

But I learned how to design content that stopped the scroll, built relationships with creators who had larger audiences than me, and got direct feedback from people who knew what worked. This was the skill-building accelerator.

Six months later, I had another decision point: take a second cohort or execute what I’d learned. I took the second cohort. That was a mistake. After the first intensive program, I knew what I needed to know. The next one was me being eager to keep learning when I should have shifted to execution.

Don’t over-consume courses.

After you have the fundamentals, it’s about reps, not more education.

But the first cohort? That was an endogenous sunk cost investment. Most creators skip it. They think consistency alone is enough. It’s not. You need strategy. You need skill-building. You need focused brand investment.

Here’s the discipline I wish I’d built on Day 1:

Brand Foundation Decisions

Why are you building your personal brand? (Not “grow followers.” What outcome does your brand enable in 12 months?)

What’s your 12-month win condition? (500 paid subscribers at $10/month? 10 inbound consulting leads from Fortune 500 companies?)

What 3 brand attributes define you? (Rigorous, Contrarian, Generous—make at least one unexpected for your category.)

What do you stand against? (Hype-driven business advice? Ahistorical thinking? Tactics without systems?)

Content Pillar Commitment

Pick 5 themes you’ll be known for. Rank them by importance. Every piece of content maps to one of these five. You’re not a generalist who talks about everything. You’re someone with a focused menu of expertise.

My pillars: business history, company operating systems, economics of firms, technology’s impact on organizations, optimizing at scale, the human side of building.

Quarterly Review Discipline

Every 90 days, ask four questions:

What worked? (Double down on this.)

What didn’t work? (Cut it.)

What did I learn? (Integrate it.)

What will I discontinue? (You’re defined by refusal as much as action.)

These choices cost you in the short term—they force you to say “no” to opportunities that don’t fit. They require discipline. They’re sunk costs.

But they’re also your moat.

The new entrant starting today faces the choice you made months ago: invest in focused brand building or compete on content volume. Most choose volume because it feels faster. By the time they realize focused brand is better, you’ve already built 12 months of compounded differentiation.

In a market of 2 million creators, you’ve already beaten 1.99 million just by showing up consistently for 12 months. Most couldn’t take the void. You did.

Bart Bronnenberg, Jean-Pierre Dubé, and Matthew Gentzkow studied consumer packaged goods across U.S. cities and discovered something remarkable: brand preferences, once formed, persist for decades.

Their question: Why do brand market shares vary so much by geography? Their answer: brand capital persists from early advertising. People who grew up with Brand X advertising prefer Brand X as adults—30+ years later.

The mechanism:

Brands advertise heavily in a market

Consumers try the brand, form habits and preferences

Even if advertising stops, preferences persist (inertia, habit, trust)

New entrants must overcome this installed base of loyalty

For creators, this dynamic is compressed but identical.

The readers who’ve followed me for 18 months have formed brand preferences about Operating by John Brewton. They’ve seen:

127 articles over 18 months (my back catalog is proof)

Consistent 5 pillars (never changing my core focus)

Quarterly reviews showing I discontinue what doesn’t serve my mission

A written “enemy” (hype-driven advice, ahistorical thinking, tactics without systems)

A new creator starting today can’t replicate this. They’d need 18 months of consistent output plus the same depth of thinking plus the same audience loyalty. The installed base of my brand capital makes it nearly impossible for new entrants to compete with me in my niche—even though entry itself is free.

Your audience builds a relationship with you over time. Every newsletter is a deposit in the “brand capital account.” Readers who’ve followed you for two years won’t switch to a new entrant easily. Your back catalog is evidence of consistency and quality that new creators can’t replicate.

Month 1: You compete with everyone.

Month 12: You have 50 posts proving consistency.

Month 24: You have 100 posts, a loyal audience, and social proof.

Month 36: New entrants can’t catch up without three years of equivalent work.

Consumer attention is zero-sum. Your subscribers have limited time. Once they’re loyal to 5-10 newsletters, they don’t add more. Early winners lock in the audience.

This explains the paradox: entry is free (new creators can start today), but success requires brand capital (which only comes from time plus consistency plus discipline). Markets concentrate around early winners who paid the cost most won’t pay.

If you understand these four papers, you know everything you need to know to understand why your creator business needs:

Daily discipline — Not because content volume is good, but because you’re training the algorithm while paying the commitment tax most won’t. This is your survival filter.

Focused brand strategy — Not because it feels faster, but because endogenous sunk cost investments create the moat most skip. Define your 5 pillars. Write your enemy statement. Commit to quarterly reviews.

Strategic discontinuation — Saying “no” compounds faster than saying “yes” to everything. Every 90 days, cut what doesn’t work. Your refusals define you as much as your commitments.

Time — Not 90 days. 12-24 months minimum. The compounding only works if you’re there to collect it.

The paradox isn’t a mystery. It’s about discipline and structure.

Low barrier to entry doesn’t mean low barrier to success. In fact, they’re inversely related. Because entry is easy, success requires extraordinary discipline in three dimensions: showing up (Stage 2), investing strategically (Stage 3), and compounding long enough to build defensibility (Stage 4).

Fifty years of economic research confirms what every successful creator discovers through experience: free entry markets concentrate around those who invest most consistently.

You’re not competing against other creators’ Day 1.

You’re competing against their Year 3.

The only way to win is to get to Year 3 yourself.

Are you willing to pay the price that 90% won’t?

- j -

In 2026, I’m working directly with 100 creators building real businesses.

I want to bring operating strategy, competitive positioning, and financial planning to a community that’s fundamentally different from my typical industrial and technology clients.

For the first 100 creator founders: Four 60-minute 1:1 advisory sessions for $95.

Context: My standard engagement starts at $10K/month. This isn’t that. This is me learning from you while helping you build something sustainable.

Limited to 100 spots. 63 of 100 have filled. Offer expires this Friday, February 6th at midnight. And once it’s gone, it will not be returning.

Academic Papers

Dixit, A. K., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1977). “Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity.” American Economic Review, 67(3), 297-308.

Seminal paper establishing the model of monopolistic competition with free entry and differentiated products

Shows how entry continues until profits reach zero in equilibrium

Foundation for understanding why low entry barriers create crowded markets

Hopenhayn, H. A. (1992). “Entry, Exit, and Firm Dynamics in Long Run Equilibrium.” Econometrica, 60(5), 1127-1150.

Models competitive industries where firms enter with uncertain productivity

Explains selection dynamics: low-productivity firms exit, high-productivity firms survive and grow

Establishes the workhorse framework for thinking about firm heterogeneity and churn in competitive markets

Sutton, J. (1991). Sunk Costs and Market Structure: Price Competition, Advertising, and the Evolution of Concentration. MIT Press.

Introduces theory of endogenous sunk costs (advertising, R&D, brand investment)

Proves that concentration remains bounded away from zero in markets with endogenous sunk costs, even as market size grows

Explains why advertising-intensive industries maintain high concentration despite low technical entry barriers

Bronnenberg, B. J., Dubé, J. P., & Gentzkow, M. (2012). “The Evolution of Brand Preferences: Evidence from Consumer Migration.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 231-270.

Uses consumer migration data to show brand preferences persist for decades

Demonstrates that brand capital accumulated through early advertising creates long-term competitive advantage

Shows how installed base of consumer loyalty creates barriers for new entrants

Supporting Research

Schmalensee, R. (1974). “Brand Loyalty and Barriers to Entry.” Southern Economic Journal, 40(4), 579-588.

Classic industrial organization paper on brand loyalty as entry barrier

Shows established brand capital creates asymmetric costs for entrants

Ailawadi, K. L., Lehmann, D. R., & Neslin, S. A. (2003). “Revenue Premium as an Outcome Measure of Brand Equity.” Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 1-17.

Operationalizes brand equity through pricing power and volume premiums

Provides empirical methods for measuring brand advantage

Market Concentration in CPG Industries

Studies on consumer packaged goods showing top 10 manufacturers capture 88% market share

Research on advertising escalation in larger markets (endogenous sunk cost evidence)

Geographic variation in brand share distribution linked to historical advertising investment

Related Articles from Operating by John Brewton

“0 to 55,000 - The First 90 Days Playbook - What I’d Do Differently Knowing What I Know Now”

Documents daily posting discipline, data tracking methodology, and monetization infrastructure decisions

Demonstrates Hopenhayn’s selection mechanism in practice

Provides empirical evidence of creator survival requirements

“The Operating Creator: Step One + Day One - Building Your Personal Brand”

Framework for brand foundation decisions (why, win condition, attributes, enemy)

Content pillar commitment methodology

Quarterly review discipline and strategic discontinuation process

Case studies of brand consistency (Obama, Nike, Patagonia, etc.)

John Brewton documents the history and future of operating companies at Operating by John Brewton. He is a graduate of Harvard University, where he studies economics. He was also a Phd student in economics at the University of Chicago. After selling his family’s B2B industrial distribution company in 2021, he has helped business owners, founders, and investors optimize their operations. He still cringes at his early LinkedIn posts and loves making content every day.

Thanks John for yet another post giving genuinely brilliant advice on how to grow as a creator. I love how you always demonstrate how you've actually walked the walk as well as talked the talk, and it's so clear that there's no such thing as a quick fix.

I draw parallels with my own practise as a poet as well. The only reason I got good at poetry, if you would allow me that slight moment of hubris, is that I practise writing every single day for 10 years. I'm trying to do the same with slow AI, and I think the results are starting to compound.

I really appreciate how you share all of your advice with everyone so generously. Charlie Munger would be proud indeed.

This is gold for creators, turning decades of economic research into actionable strategies makes the high barriers to success feel navigable.